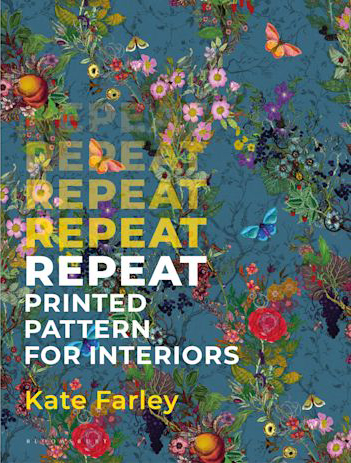

Here we are, the book project is complete with publication in the UK and US today. It’s been a journey!

With the first thoughts of writing a book about pattern back in late 2015, the development of some draft scopes, the contract signed with Bloomsbury in early 2019, a first draft of Chapter 1 delivered in late 2019, a global pandemic from 2020, unscheduled health issues requiring hospitalisation & surgery in 20/21, final manuscript submitted in June 2021, and proofreading / layout until June 2022 I have had to be very focused and patient – and all this while leading two degree courses until this Autumn (I now only lead one!).

Writing a design book had never previously been a consideration of mine, but since I’d been reviewing books a few years ago it got me thinking that this was the perfect place to bring together my design practice experience with my academic role. The idea grew on me. I’ve spent years teaching pattern design and as a result tried and tested hundreds of ways to deliver inspiring and informative design workshops. I spend lots of time analysing pattern to support my lectures, and in my spare time … and so in hindsight maybe it was a natural next step.

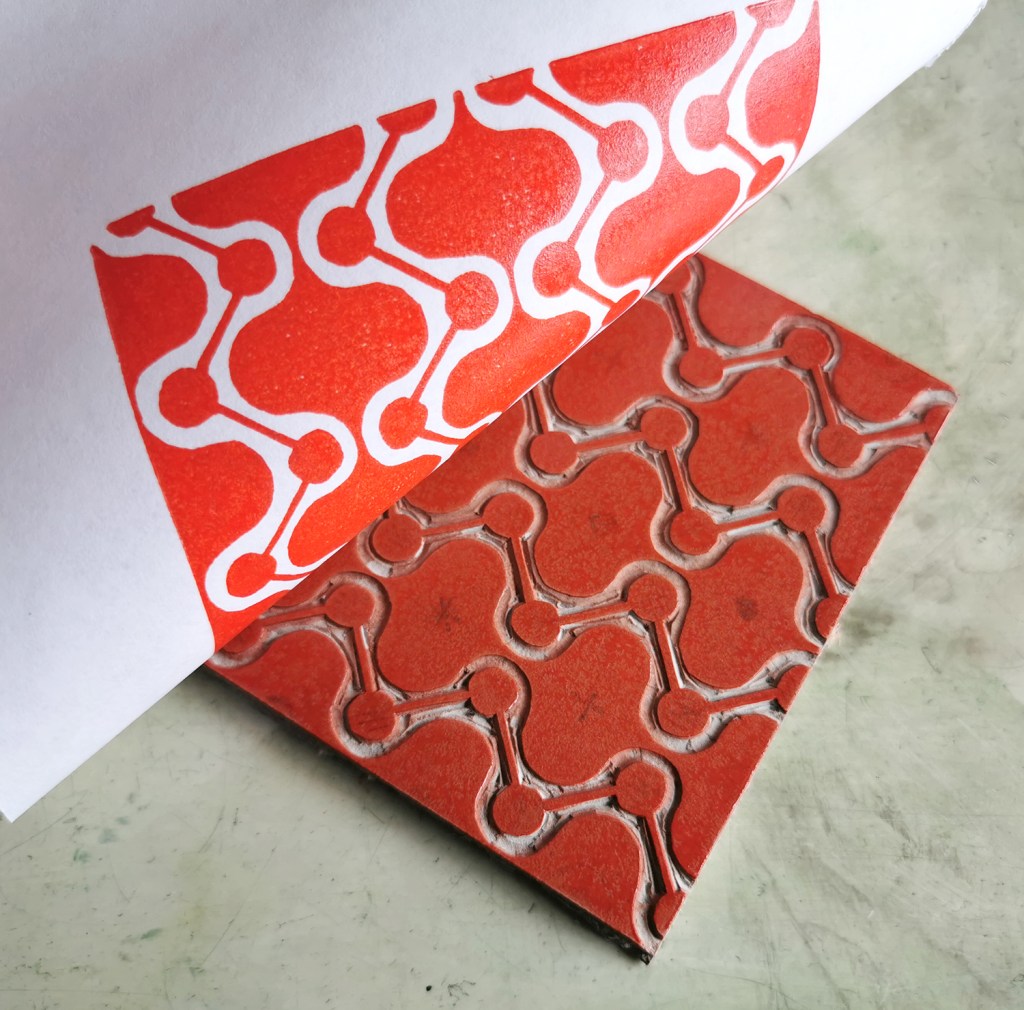

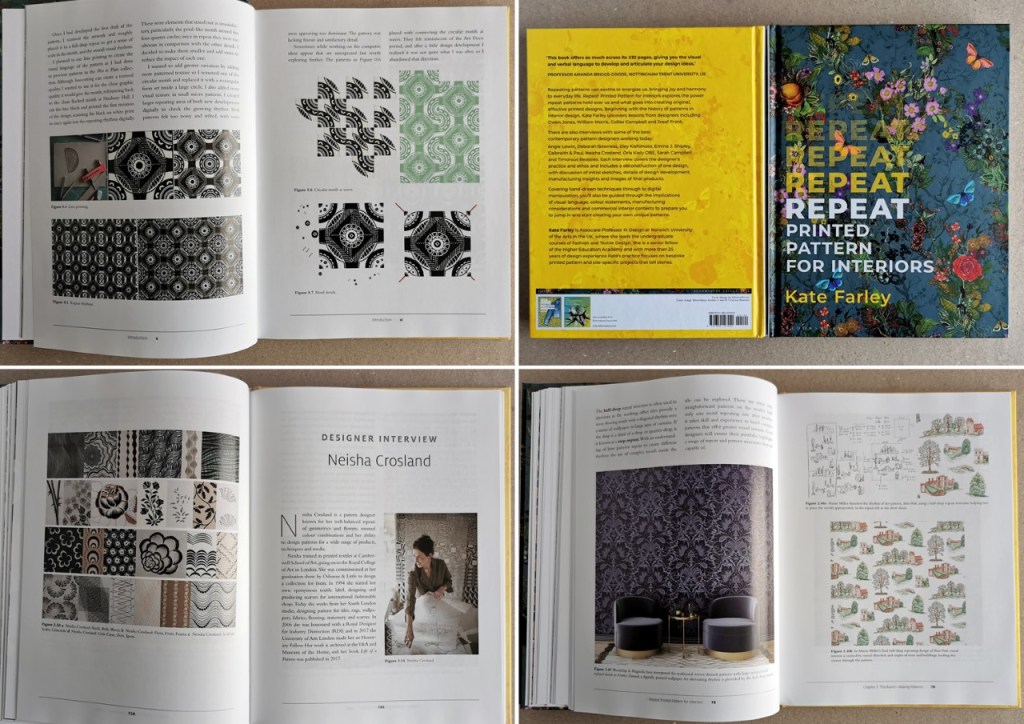

The introduction includes me taking the reader through my journey of designing Hanbury, my wallpaper, as well as my relationship with pattern. The three chapters are very different in nature which helped to focus the research and writing at each stage, and provides the reader with a broad look at the subject of pattern design in relation to history – Chapter 1, how to create pattern – Chapter 2, and how others do, through nine feature interviews in Chapter 3. I have to comment on the cover … I love the cover, so a huge shout out to Paul and Ali of Timorous Beasties and to my publisher Georgia at Bloomsbury who allowed me to have it just as I wanted. In fact I owe so much of this project to Georgia’s belief in me to get this done, and her unwavering support throughout. Who’d be a publisher?

Many years ago a previous boss asked me to take on delivering the design history lectures to first year undergraduates and with panic and fear I embarked on what I can now describe as one of the most overwhelmingly frightening but important career defining undertakings. I was given an opportunity to challenge myself while presenting to a lecture theatre of students on a Friday morning in Birmingham, and the result was empowerment. Without high school History qualifications behind me but a passion and base knowledge of design history I decided to engage students in how history is relevant to us now, what we can learn from, challenge and move on from. I needed it to be immediately relevant to their design projects to help them understand history is important to designers today. It took some years before I felt on top of it, but many years on I comprehend the legacy of those hours of learning in order to teach, and how that substantial investment of time led to the knowledge and experience to write Chapter 1 of this book. I could have written many thousands of words more to cover the history of pattern across the globe, but word limits provided boundaries, and without a deadline I may still be writing!

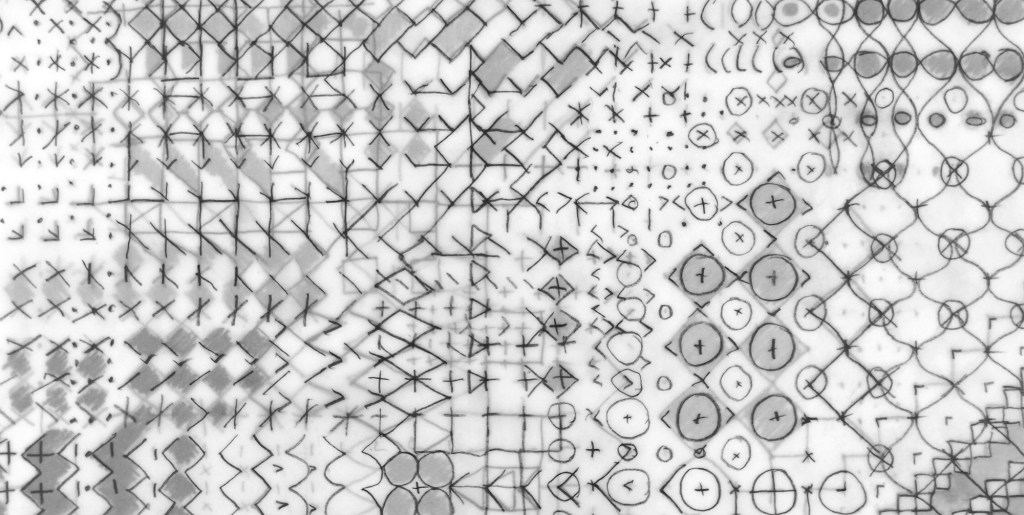

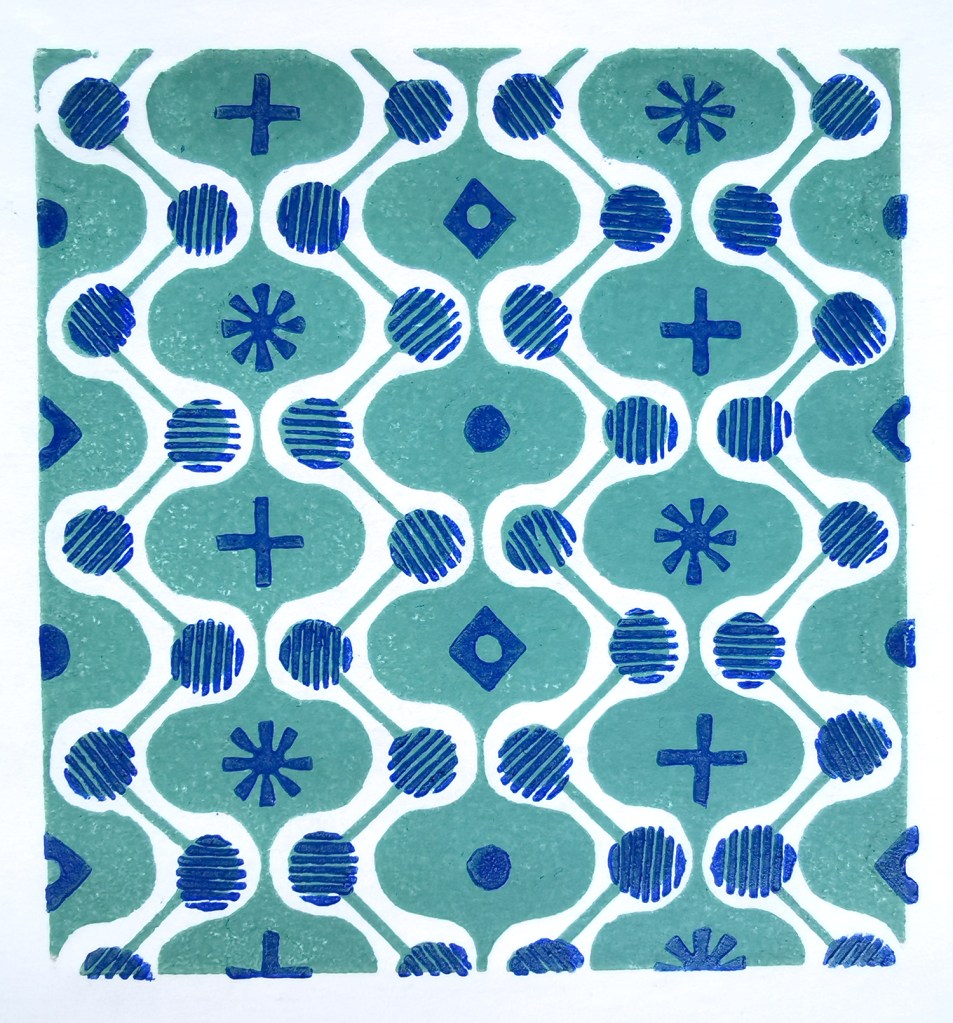

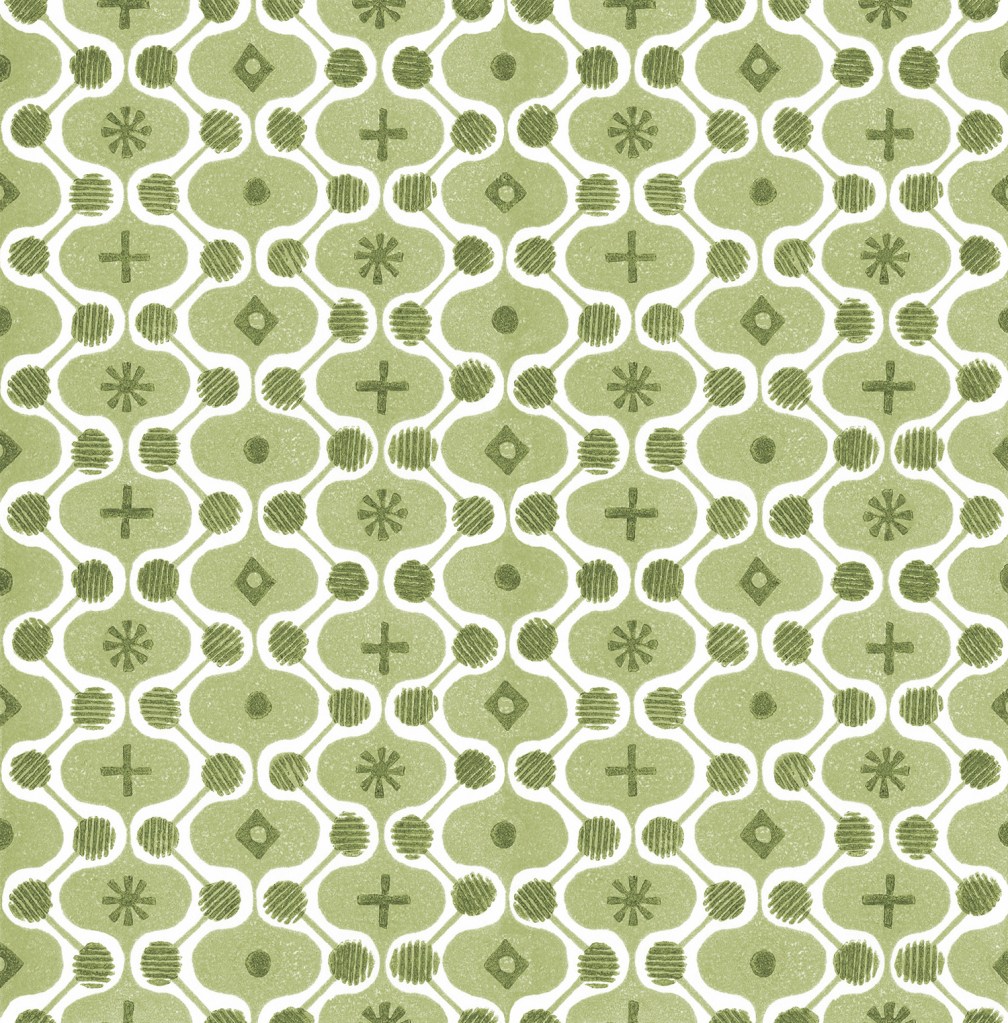

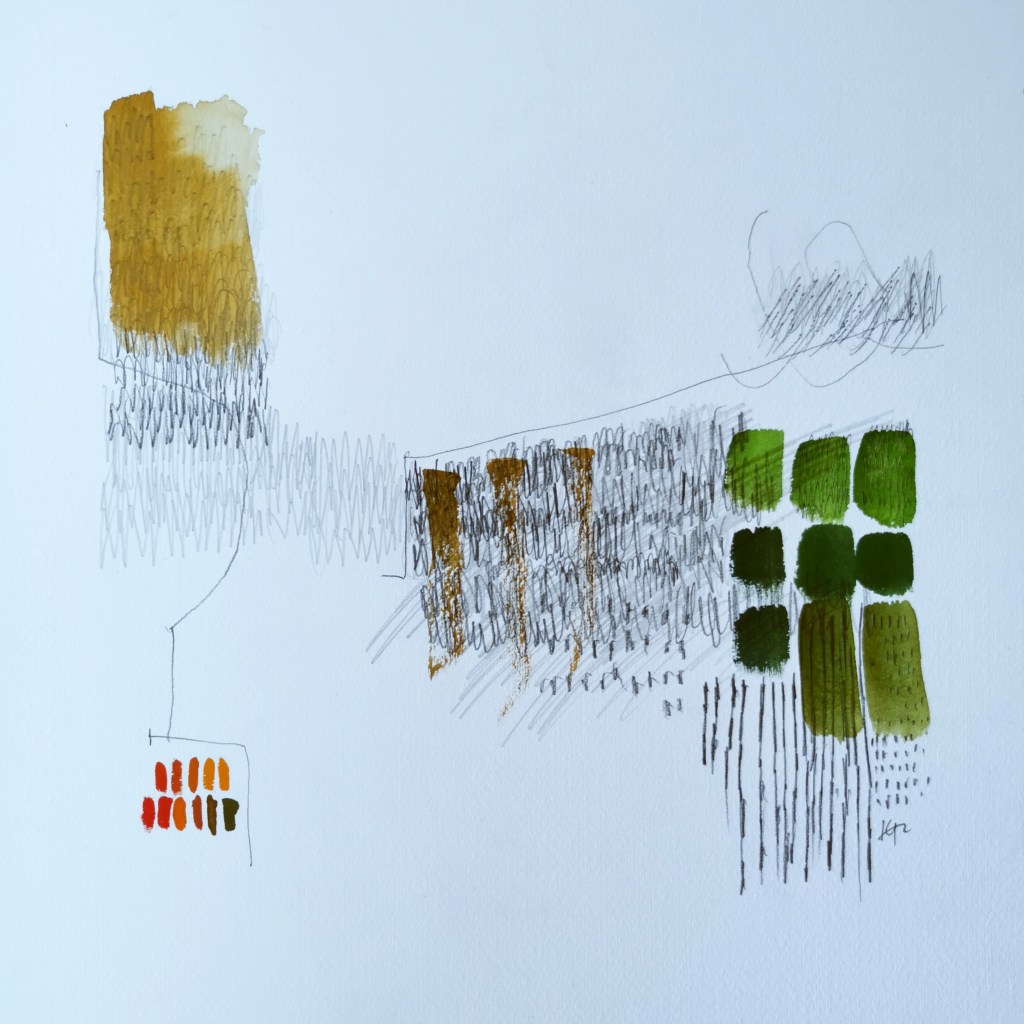

I enjoy learning. I am hugely grateful to all the students I have had the pleasure to work with over the years, for sharing their creative journeys as we discuss drawing, rhythms, compositions and colour proportions to make the most interesting repeating outcomes. I’ve learned so much along the way, and that’s what keeps me interested and passionate about the discipline of pattern design. Every studio session is an exchanging of ideas, with no single correct answer, but plenty of opportunities – a privilege to be a part of, and the inspiration behind Chapter 2. It explores the practice of repeat pattern making, presenting considerations to build stronger outcomes without stipulating one right answer. I encourage designers to embrace the process of testing variations in pattern construction so the final result has learned from all that has gone before. The designers I include to illustrate the text offer so many styles and approaches and have been so generous in sharing their working practice with me and future readers.

Just as I did with my degree dissertation back in 1996/97 there were times that required drastic measures to get things right in the writing of the book – many sheets of paper were laid out across the floor and I took scissors to the pages, literally cutting and pasting paragraphs in the process of reordering the narrative. Other times I had to diligently input data on a spreadsheet, chase consent forms or simply focus on writing.

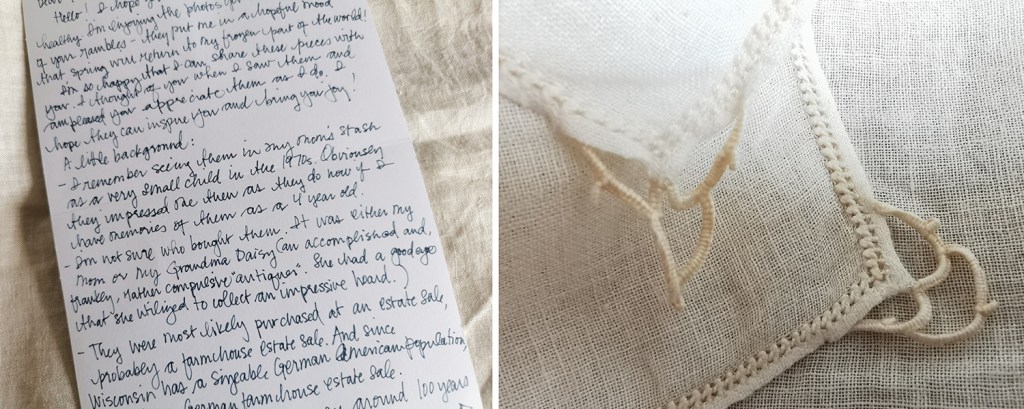

Obtaining image permissions was probably the most arduous and stressful process of the project. Keeping to budget while securing the images from archives, individuals, estates and designers I really wished for was difficult, and sometimes I had to admit defeat and find alternatives. My editor and publisher (Faith & Georgia) were both brilliant at talking this over and I’ve been so pleased to include some absolute favourites such as Lucienne Day’s Spectators and Calyx and Josef Frank’s Mirakel – I danced when these came through! It’s also been a pleasure to include a number of works by students I have taught, some in the last five years, but also Emma J Shipley back in 2005/6 – I still remember her tour bus interior for Madonna in BA1 (one of the interviewees in Chapter 3). How time flies!

I’m grateful to all the designers / archivists who have contributed images and details of the patterns throughout the book. Quick check-ins to confirm the number of screens used, or what digital software the designer prefers was all part and parcel of getting details as correct as possible. One memorable highlight on a day of writing was a phone call from the brilliant pattern designer Marthe Armitage to talk through her contributing images for the book. I was so surprised I was rather lost for words initially, but soon we were chatting all things pattern, and I’m delighted to feature her printed wallpaper patterns in the book, as they regularly feature in my teaching presentations. A shout out goes to Sophie at Warner Textile Archive who went above and beyond tolerating last minute requests for photography to get just what I wanted! Much of my clear headed thinking happened late at night as I juggled leading two courses in the day job, and I’m grateful for all who made sense of my communications at this time.

Who knew it took so long and so many people to get a book to be a physical artefact? The proof reader was brilliant as we fired queries and answers to and fro for a frantic few weeks, and then she was gone. Then the layout was taking shape – and I think I must have been a nightmare – sorry Deborah! – I wanted every page to look its best and sent diagrams and descriptions to make that happen. Finally, following last minute queries while I was at New Designers showcase in London with my graduates in late June I had to step away and the book went off for print production.

I’ve been asked several times if there will be a second book, even before I held this one in my hands…! I’m not sure, maybe one day, but today I’m celebrating this one.

I’m grateful to all who have helped make this happen, from my tutors back at art school, to friends and colleagues who have tolerated and supported me in this project. Thanks to the brilliant team and associated individuals from team Bloomsbury and to everyone who buys a copy to share the joy of printed pattern – thank you!

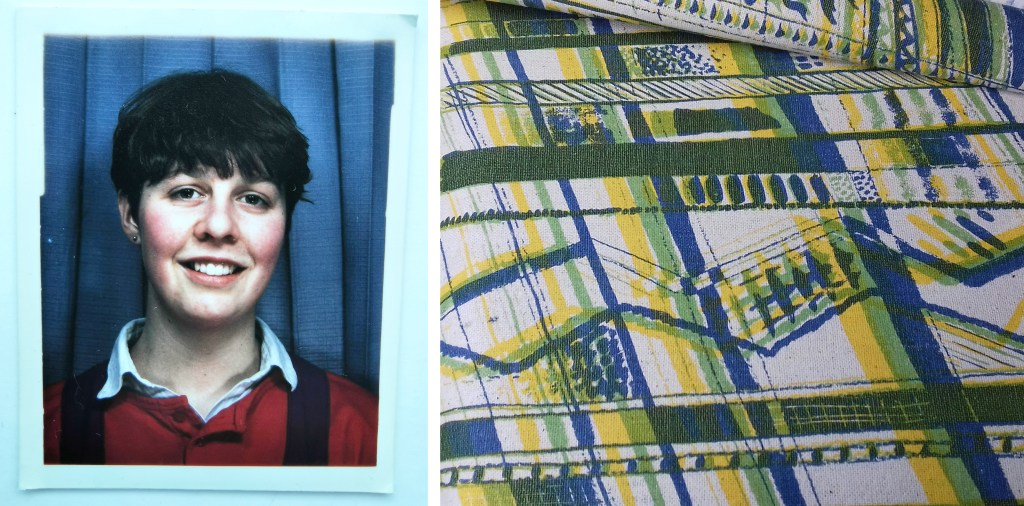

I’d like to dedicate the book to my parents in deepest gratitude for providing an upbringing where experiencing art, design & culture was a given. Thanks to my mum who has survived the ups and downs of raising a creative child, I know it wasn’t always easy. My sorrow remains that I never had the chance to have an adult to adult conversation with my dad about the things we would have no doubt had as common passions, but who inadvertently taught us Farley girls that if you put your mind to something there is no reason why it won’t work out. A lasting legacy & mindset.

You can order a copy here.